Morrison Formation

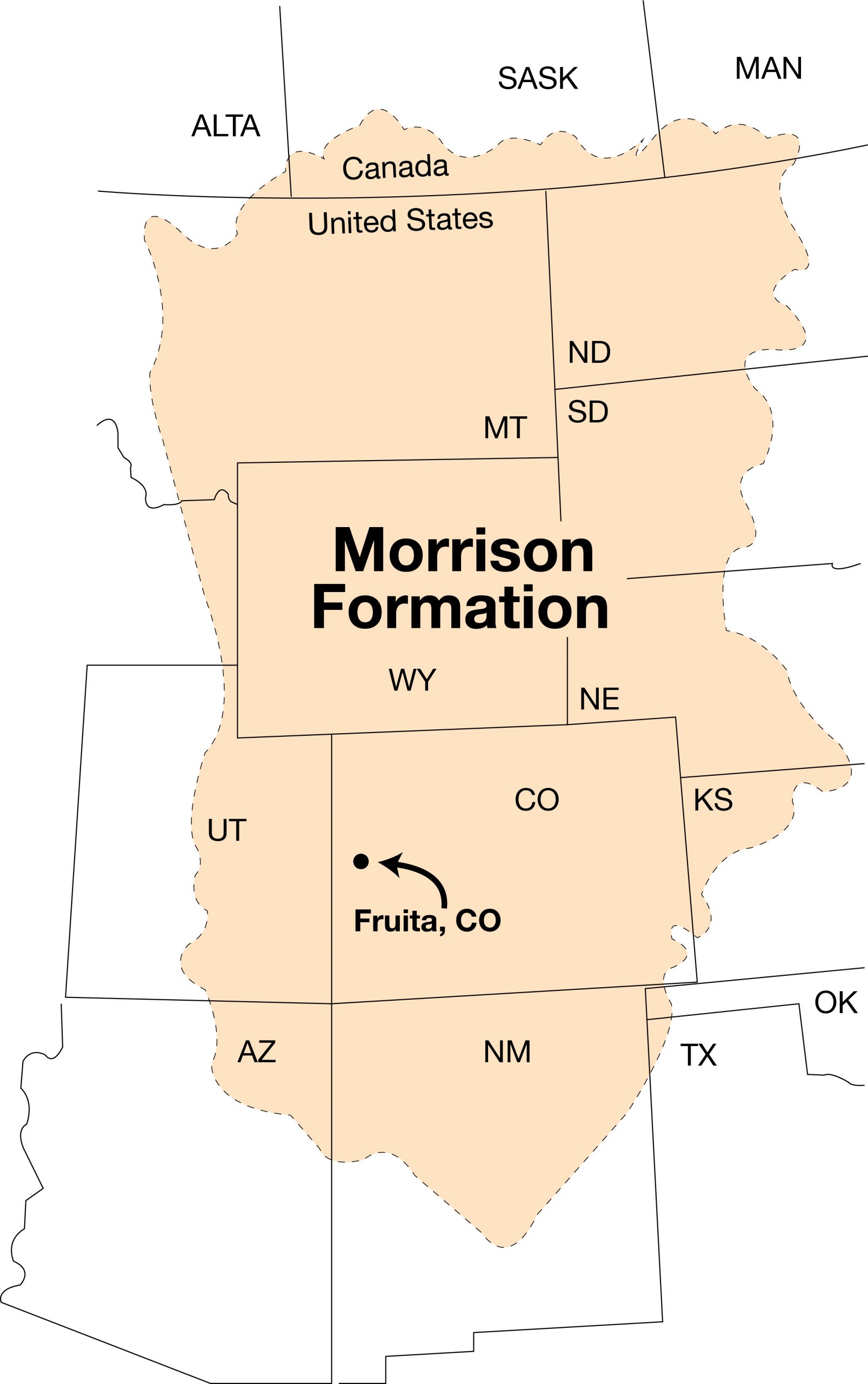

While the Morrison Formation was deposited 156.3 – 146.8 million years ago (mya), the world looked quite different than it does today. Globally, the supercontinent of Pangea that formed in the Permian Period began its split in the Triassic Period and continued into the Jurassic Period. By the beginning of the Jurassic (201.3 mya), the landmass in the northern  hemisphere split into North America and Eurasia, but both continents were still connected by land bridges by the late Jurassic.

hemisphere split into North America and Eurasia, but both continents were still connected by land bridges by the late Jurassic.

Regionally, many of the features that define the Grand Valley had not formed yet. The Mancos Formation that makes up the majority of the Bookcliffs had not been deposited, nor had the Uncompahgre uplift that created Colorado National Monument occurred and the Rocky Mountains to the east had yet to form. Instead, the area was part of a broad, lowland river basin.

The Morrison Basin extended from New Mexico in the south to Alberta and Saskatchewan in the north and was formed when mountain ranges began to lift along the western margin of North America. As the mountains grew in the southwest, a shallow inland sea, called the Sundance Sea, covered the area and began to drain the rivers running to the north off the southwestern mountains. These mountains created a rain shadow, causing the region to become arid, while rivers draining the mountain ranges to the south and southwest filled the basin with sediment. The Morrison Formation consists of these sediments deposited by this massive river system including not only the river channels, but all of the associated floodplains, ponds, and salt flats that would have surrounded them. The variety of ecosystems that created the Morrison Formation would have resembled those we see today in the Mississippi River Valley, but in a wet-dry seasonal climate.

In the Grand Valley, the Morrison Formation is subdivided into three members:

| Brushy Basin: Youngest member of the Morrison Formation that consists of clay rich badlands and sandy river deposits formed as volcanism in the mountains spewed ash that choked rivers and streams. This ash is also a source of uranium and bentonite deposits in the Colorado Plateau. |

| Salt Wash: Middle member of the Morrison Formation consisting of sands and gravels deposited as seasonal rains in the mountains flowed downstream, and small pockets of muddy shales from the floodplains. |

| Tidwell: Oldest member of the Morrison Formation consisting of mudstone and sandstone layers deposited by muddy tidal flats and sandy shorelines as the Sundance Sea drained. |

Dinosaur fossils are most common in the Brushy Basin Member and are rare in the lower members of the Morrison.

If you want to learn more about other geologic formations found in the Grand Valley see: Geology and Paleontology of the Grand Valley

Common Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation

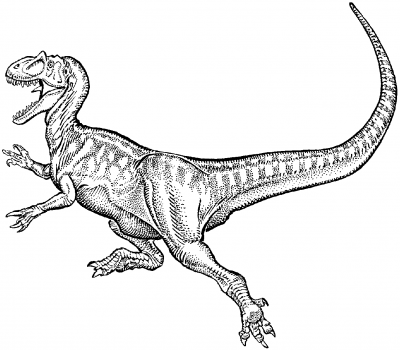

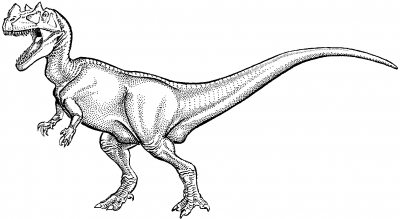

Allosaurus

Allosaurus was not the largest meat-eating dinosaur from the Morrison Formation, but it was the most common. It is also the most common predatory dinosaur found in the entire Grand Valley.

Allosaurus was a 25-30-foot long dinosaur that roamed western Colorado (and most of the American west). It was a powerful predator that preyed upon a variety of animals, from small two-legged plant eaters to Stegosaurus and sauropods like Apatosaurus. It had a skull that was over two feet long and contained dozens of sharp, serrated teeth, while its arms were muscular and ended in three sharp claws.

The skull of Allosaurus was strong and well-built, despite appearing hollow. Its bite force was relatively weak for an animal its size–on par with a modern American alligator. Ball and socket joints between the neck bones, along with powerful muscles would have allowed Allosaurus to move its head like a hatchet, slamming down into its prey or food with tremendous force, similar to how hawks and eagles feed on prey today. Its ears were adapted to pick up deep sounds like modern crocodilians do. This also means that Allosaurus was likely able to make sounds deeper than humans can hear.

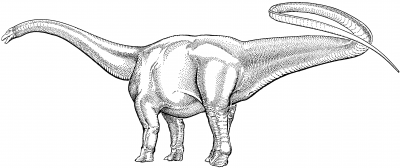

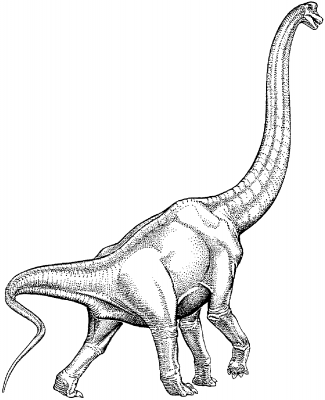

Apatosaurus

Apatosaurus is the most common dinosaur found at the Mygatt-Moore Quarry in Rabbit Valley. It is also the most common dinosaur found in the entire Grand Valley. The average size of Apatosaurus is 65 feet long; however, at Mygatt-Moore the remains of an Apatosaurus over 80 feet long and those of young animals barely 20 feet long have been found. Apatosaurus belongs to a group of dinosaurs called sauropods. Sauropods are characterized by their long necks and tails. Like all sauropods, Apatosaurus was an herbivore. According to research by Dinosaur Journey Curator of Paleontology, Dr. Julia McHugh, Apatosaurus was a low browser that ate tough vegetation like conifers, and cycads.

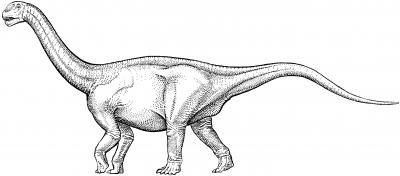

Camarasaurus

Camarasaurus is the most common sauropod found in the Morrison Formation. It was also the first dinosaur dug up in the Grand Valley. Paleontologist Elmer Riggs and his crew dug up a partial skeleton on the flanks of Colorado National Monument just days before discovering the Brachiosaurus quarry at Riggs Hill. It could grow up to 60 ft in length, and has a skull adapted to eating plants. The broad, spoon-shaped teeth would not have been good at processing small plants either. With its long neck and big, blunt teeth, Camarasaurus was probably best suited for pulling off larger parts of trees, browsing at shoulder height, or higher.

Ceratosaurus

Ceratosaurus is a type of theropod dinosaur that is also found in the Morrison Formation. It’s also the official fossil of Fruita, Colorado. Like all theropods, Ceratosaurus walked on two powerful hind legs and had much smaller forelimbs. Much smaller than Allosaurus, Ceratosaurus only reached lengths of up to 18 feet long. Ceratosaurus would have had four fingers on its hand, whereas fellow theropod, Allosaurus, would have only had three. Its skull had proportionally long, blade-like serrated teeth and a prominent horn on its snout. The presence of osteoderms (skin bones) running along its back and tail gave it a more reptile-like appearance.

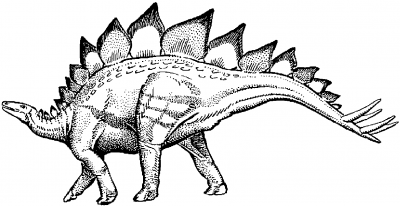

Stegosaurus

Stegosaurus was declared Colorado’s state fossil in 1982. It has been found throughout Colorado, from the Front Range to the Grand Valley. The series of plates along its back and tail make this dinosaur easily recognizable. Scientists still debate the purpose of those plates. Some ideas include display or use in controlling body temperature. There is less debate about the spikes on its tail, which are believed to have been used for defense. Stegosaurus also had shorter forelimbs and longer hind limbs. Because of this it is believed to have eaten vegetation less than 3 ft (1 m) above the ground.

Riggs Hill

In 1900, Elmer Riggs, a paleontologist at Chicago’s Field Columbian Museum (now known as the Field Museum of Natural History), set out to the Grand Valley to collect dinosaurs. Led here through correspondence from Dr. S.M. Bradbury of Grand Junction, Riggs was inspired by the news that ranchers had been collecting fossils in this area since it was first settled in the 1880s.

On the south slope of this hill in rocks of the Morrison Formation, Riggs and his field assistants discovered and excavated a previously unknown dinosaur. Riggs assigned the name of Brachiosaurus altithorax (deep-chest arm-lizard) because the front legs were much longer than those in the back and the ribs were nearly 9 feet long. In honor of Riggs’ discovery, this hill was named after him, and the site of his quarry is marked with a stone monument.

The dinosaur specimen was discovered on July 4, 1900, but work on it did not begin until three weeks later because Riggs and his crew were finishing work at another site near what is now the east entrance to Colorado National Monument. Riggs recognized very quickly that what they had found was at the time the largest dinosaur known. It remained the largest known for 70 years. The crew took about six weeks to dig up the dinosaur, and by mid-September they were on their way back to Chicago.

In 1937 on the northwest slope of this hill, Edward Holt discovered partial skeletons of Allosaurus and Stegosaurus. Hoping the area would become a natural research center, Holt left the bones in the rock. Unfortunately, the bones and other scientific information have been lost through vandalism.

Brachiosaurus was a gigantic (43-ton) sauropod dinosaur and one of the rarest dinosaurs in the Morrison Formation. Unlike most sauropods, however, the front legs of Brachiosaurus were very long, its tail relatively short, its chest very deep, and its neck rather long as well. These characteristics and the fact that its teeth were those of a plant-eater suggest that Brachiosaurus was the Late Jurassic equivalent of a giraffe, feeding high in the treetops. With its head 41 feet (12.5 meters) off the ground, Brachiosaurus certainly would have had its pick of the finest treetop morsels. |

Click photos to enlarge.

Dinosaur Hill

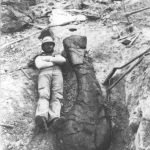

Elmer Riggs and his crew of one field assistant/photographer and a field assistant/camp cook excavated a quarry on the east side of Dinosaur Hill during the summer of 1901. The previous year, the crew had excavated the first Brachiosaurus ever discovered from Riggs Hill. The crew camped under cottonwood trees along the banks of the Colorado River and worked the dinosaur quarry each day. The crew would have to ferry both equipment and bones across the river. Unfortunately, during one of the trips across the river, the ferry capsized and lost a lot of their field equipment. When the dinosaur they were chasing turned out to run straight into Dinosaur Hill, they enlisted the help of local miners to blast a tunnel into the hillside. They found the back half of the skeleton of a 70-foot-long plant-eating dinosaur called Apatosaurus at this quarry. This skeleton is still mounted at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

Elmer Riggs was intrigued by this skeleton and began a study of these animals and others similar to it. Based his results, he concluded in 1903 that Apatosaurus and “Brontosaurus” were two names for the same type of animal, the only differences were changes in the skeleton due to age. And since the name Apatosaurus had been published first, it had priority, and the name “Brontosaurus” was no longer valid. However, the name persisted in pop culture long after that. Riggs considered his work at Dinosaur Hill to be the most important of his career

In 1992 the original mine was reopened by paleontologists at Museums of Western Colorado at great expense to ensure safety. A second quarry was excavated on west side of Dinosaur Hill by Museums of Western Colorado scientists in 2004, and they found an assortment of animal fossils from the same rocks as Riggs’ Apatosaurus quarry. These included a juvenile Camarasaurus, a juvenile Stegosaurus, turtles, crocodiles, meat-eating dinosaurs, a small lizard-like reptile called a sphenodontid, and a specimen of the rare flying reptiles known as pterosaurs. All these were found in a quarry the size of a dining-room table!

Click photos to enlarge.

Fruita Paleontological Area

The Fruita Paleontological Area (FPA) is a half-mile square area outside of the town of Fruita, Colorado and is within the McInnis Canyons National Conservation Area. As early as 1891, fossils from the FPA were reported in the local newspaper. The bones found were misidentified as “mammoth bones” because of their size, but they were actually dinosaur bones. Local amateur geologist and newspaper man, Al Look took to promoting the region’s geological and paleontological resources, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that rigorous scientific research began at the FPA.

Concerns over vandalism and fossil theft prompted Curator of Paleontology, Lance Eriksen, from the Historical Museum Institute of Western Colorado (now the Museums of Western Colorado) to apply for a permit and begin collecting fossils in 1976. The fossils that he collected became some of the first fossils in the museum’s collection. These include the skull and partial skeleton of Ceratosaurus, as well as Stegosaurus and Allosaurus fossils.

In 1975, a field crew from California State University, Long Beach led by paleontologist George Callison visited the area and began collecting microfossils. Microfossils are exceedingly rare from the Jurassic Period. The abundance of microfossils made the area famous and as a result, the FPA was established as a protected area for fossil resources by the BLM in 1977.

Paleoenvironment

There is evidence that more than twelve river channels left deposits within the FPA. These ancient rivers originated in the mountain ranges to the south and west and flowed to the northeast and were prone to flooding in the rainy season. However, most of the fossil story of the FPA is tied to two river channels. One of these river channels is named Fruita Croc River Channel, after the small fossils of an early crocodile relative, Fruitachampsa callisoni, that have been found inside it. The other river channel has been named Ceratosaurus River Channel, named for the dinosaur Ceratosaurus “magnicornis” found in 1976 by the Museums of Western Colorado.

Within the FPA are also two active quarries known for producing microfossils; these are Callison Quarry and Tom’s Place Quarry. Here small vertebrates such as chipmunk-sized mammal, Fruitafossor, the early snake, Diablophis, and the long-legged crocodylomorph, Fruitachampsa can be found among with many others. While large animals like dinosaurs are exciting to find, the smaller animals and plants often give scientists a more detailed picture of what life was like at a specific location. Large animals may travel great distances to meet their nutritional needs, whereas, small animals do not travel quite as far. As a result, looking at the small plants and animals can help scientists figure out the big picture of a place.

The FPA is unique for having preserved a variety of fossils both large and small. These include freshwater snails and clams, crayfish, caddisfly cases, clam shrimp, frogs, turtles, and the remains of a 10-12-foot long aquatic crocodylomorph. Terrestrial fossils from the FPA include: trace fossils such as footprints, egg shells, and burrows, three kinds of rhynchocephalians (lizard relatives), five types of lizard, one snake, a 2-3-foot long terrestrial crocodylomorph, ten types of mammal and mammal relatives, one pterosaur, two theropod dinosaurs, two sauropod dinosaurs, and three ornithischian dinosaurs.

Fruitadens is the smallest ornithischian dinosaur yet discovered. The largest individuals are estimated to have been about 26 to 30 in (67 to 75 cm) long and weighed 1.1 to 1.7 lbs. (0.5 to 0.75 kg). It was named after the town of Fruita, because it was discovered in the nearby Fruita Paleontological Area by George Callison and his crew. Fruitadens ate plants and possibly insects and other invertebrates. |

Click photos to enlarge.

Mygatt-Moore Quarry

The Mygatt-Moore Quarry was discovered on March 14, 1981 when two couples, John “J.D.” and Vanetta Moore along with Pete and Marilyn Mygatt, came across the area while hiking. The site is located just outside Fruita, Colorado in the northwestern part of Rabbit Valley. It has been worked every summer since 1985 and has produced more than 2,300 mapped bones.

Paleoenvironment

The muddy sediments of the Mygatt-Moore Quarry were deposited in the flat floodplains near a river, perhaps as a quiet, seasonal pond or watering hole during the Jurassic Period. Fine layers of shale, called laminated beds, show that muddy sediments accumulated very slowly and seasonally. Parts of the shale layers change abruptly from these laminated beds to thick (4-6 inches) blocks of mudstone. This tells scientists that when the mud was still wet, and not yet turned to stone, dinosaurs stomped through the area, churning up the mud and destroying those fine layers.

A large number of vertebrate animal remains have been discovered at Mygatt-Moore. Along with fish, found in the layer above the main quarry, and crocodilians which are exceedingly rare at this site, there have been a number of dinosaurs including: Ceratosaurus, Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus, Mymoorapelta, and Nanosaurus. Of these, an unusual abundance of Allosaurus and Apatosaurus have been found. Many of the bones show indications of trampling and abundant scavenging from predators like Allosaurus, indicating that the area was visited frequently and that animals were not buried rapidly when they died. This delayed burial tells scientists that animals were not trapped at Mygatt-Moore in a catastrophic event. Instead, the bones accumulated gradually over time.

Delicate material like dinosaur skin, tiny bones of amphibians and lizard-relatives, and dinosaur eggshell have also been preserved here. Along with the remains of vertebrate animals, plant material from ferns, conifers, gingkoes, horsetails and cycads have been found in the form of pollen, wood, cones, and short shoots. Invertebrate animals including gastropods and crayfish (from the layer above the main quarry) have also been recovered.

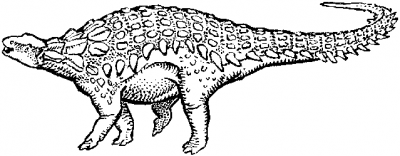

Armored dinosaurs were rare during the Jurassic Period, but became more common in the Cretaceous Period. Mymoorapelta was first found at the Mygatt-Moore Quarry in Rabbit Valley and was also the first ankylosaur found in the Jurassic Period. It had short legs and a heavy build, weighing around 1,100 lbs. (500 kg). For defense it had bony armor and sharp spines embedded in its skin. Mymoorapelta was an herbivore that most likely spent its time eating low-growing vegetation. |

Click photos to enlarge.

Visit with Respect

All of the above fossil sites are co-managed by the BLM and Museums of Western Colorado and can be accessed by hiking trails.

Dinosaur Hill Interpretive Trail Guide

Dinosaur Trails in the Fruita Area

When visiting these sites and others like them, it is important to practice good stewardship of the land and respect the fossil resources contained within.

Fossils and tracks are protected under the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act (PRPA) of 2009. The act prohibits an attempt to excavate, remove, damage, or otherwise alter or deface any paleontological resources located on Federal land.

| Landowner | Type of Fossil | Is fossil collecting allowed? |

| National Park Service | Plants | Permit Required |

| Invertebrates | Permit Required | |

| Vertebrates | Permit Required | |

| BLM | Plants | Yes, but restrictions apply |

| Invertebrates | Yes, but restrictions apply | |

| Vertebrates | Permit Required | |

| National Conservation Areas: McInnis Canyon, Dominguez-Escalante & Gunnison Gorge | Plants, Invertebrates, Vertebrates | Permit Required |

| US Forest Service | Plants | Yes, but restrictions apply |

| Invertebrates | Yes, but restrictions apply | |

| Vertebrates | Permit Required | |

| State Parks | Plants | Permit Required |

| Invertebrates | Permit Required | |

| Vertebrates | Permit Required | |

| Private | Plants | Landowner Permission Required |

| Invertebrates | Landowner Permission Required | |

| Vertebrates | Landowner Permission Required |

Why can’t I collect vertebrate fossils?

Vertebrate fossils are rare compared to plant and invertebrate fossils. Scientists can learn a lot by finding the fossil in its original context. When someone removes a fossil, that context is lost along with all of the important scientific information.

Why can’t I collect fossils anywhere I want?

The Paleontological Resources Preservation Act (PRPA) is the United States law preserving paleontological resources on federal land. This act protects scientifically significant fossils on federal land against vandals and the abuse of fossils at the expense of scientific discovery.

What do you do when you find a fossil you don’t have permission to collect?

Take a picture and GPS coordinates if possible and give that information to a Park or BLM Ranger or a paleontologist at a local museum but be sure to leave the fossil where you found it.