Agricultural goods such as livestock, fruits and wine have been beneficial staples of Western Colorado’s economy. The other not so stable part of the economy has been the mining industry. Mining for specific minerals has always been followed by waves of economic and population booms followed by devastating. Fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas continue to be extracted in rural parts of the Colorado Plateau, but there is another mineral that has been historically sought out and is worth millions. It is neither gold nor silver, but uranium.

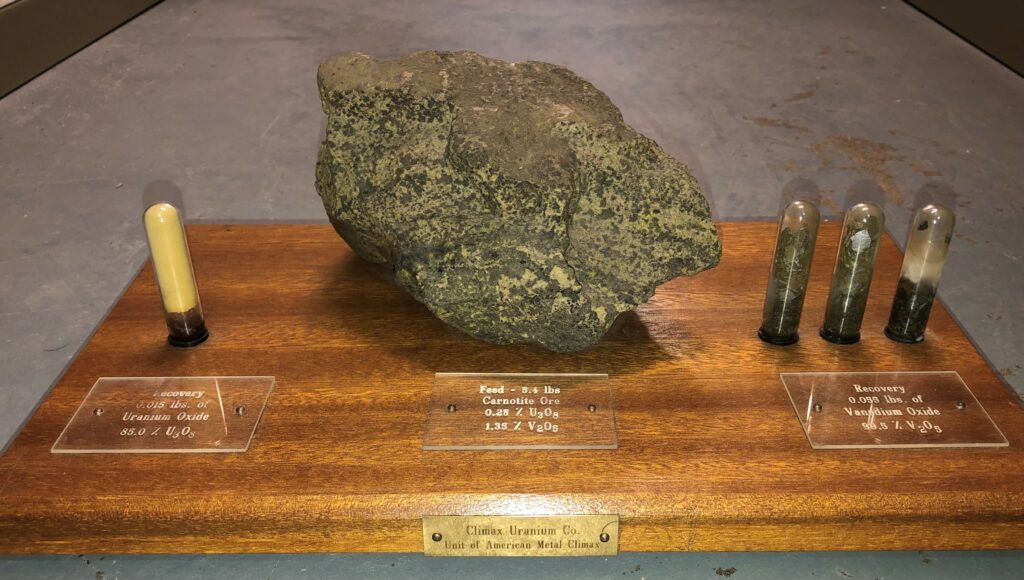

Since 1898, the Colorado Plateau has been a central hub for prospectors, miners, scientists, and companies to profit from the rich minerals beneath the surface. Many booms came from the use and study of radioactivity, specifically that of uranium and radium. These minerals are often found within carnotite compound along with vanadium. Moab was one of the many self-proclaimed uranium capitals of the world, resting along the Morrison geological formation, a hotbed for carnotite fissures.

Bibliography

Amundson, Michael A. Yellowcake Towns: Uranium Mining Communities in the American West. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 2004.

Atomic Energy Commission. Prospecting for Uranium. Washington DC: Atomic Energy Commission, 1951

Chenoweth, William. “The Manhattan Project in Mesa County.” July 1984.

Chenoweth, William. “Uranium in Western Colorado.” The Mountain Geologist 14, no. 3 (July 1978): 89-95.

Huleatt, W.P., Hazen Jr., Scott W., Traver Jr., William M. Report of Investigation: Exploration of Vanadium Region of Western Colorado and Eastern Utah. US Department of the Interior, September 1946.

Look, Alfred. U-Boom: Uranium on the Colorado Plateau. Denver: Bell Press, 1956.

Lubenau, Joel, and Edward Landa. Radium City: A History of America’s First Nuclear Industry. Pittsburgh: Heinz History Center, 2019.

McMillan, Steve. “GJ may get some help with pool: mill tailings may force DOE to help pay bill.” The Daily Sentinel, March 6, 1985.

Moore, Jean. Unaweep Canyon: At Some Point in Time. Decorah, IA: Anundsen Publishing Co., 2000.

Rice, Ginger. “Tailings work boon to area economy.” The Daily Sentinel, July 17, 1990.

Smithsonian Institution Online Collection. https://www.si.edu/object/piper-pa-18-super-cub%3Anasm_A19761155000

Sullenberger, Robert. “100 Years of Uranium Activity in the Four Corners Region.” Journal of the Western Slope 7, no. 4 (Fall 1992): 2.

US Atomic Energy Commission. Report of Practicability Study & Cost Estimate Removal of Uranium Mill Tailings from under or near certain residences in the Grand Junction, Colorado Area. Grand Junction, CO: AEC, 1971.

US Congress. House. Hearing before the Subcommittee on Raw Materials of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy. 92nd Cong, 1st sess., 1971.

US Department of Energy. Environmental Assessment of Ground Water Compliance at the Grand Junction UMTRA Project Site. Grand Junction, CO: Department of Energy: 1999.

Webb, Dennis. “Trump signed bill extends life of area mill tailings disposal site.” The Daily Sentinel, December 29, 2020.

Supported in part by an award from the Colorado Historical Records Advisory Board, through funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC), National Archives Records Administration.

Additionally, the William Chenoweth Collection, which includes a variety of materials relating to the history of uranium in western Colorado, was catalogued and digitized as part of the grant. Soon, you’ll be able to view these items online!